August, Grief, and Storytelling

Sharing about my experience speaking at the 9/11 Memorial & Museum

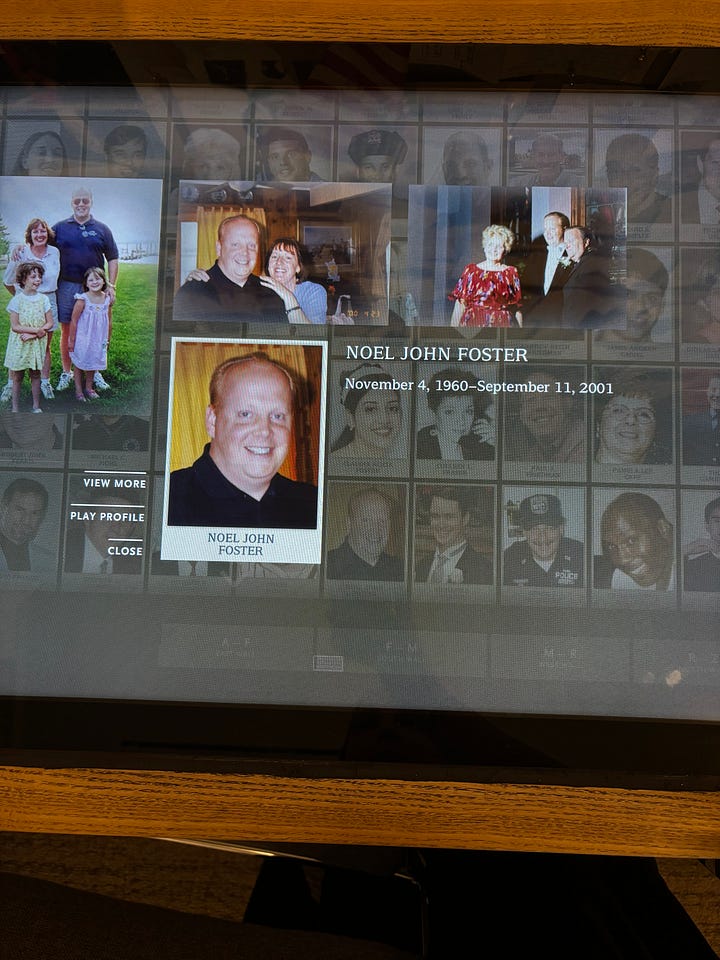

Ever since I was six, guilt would swell up inside me when August hit. Summer days were escaping quickly. As if grabbing a handful of sand at the beach and watching the minuscule grains of sand run through my fingers, my childhood days of carefree wonder were slipping away. August is a reminder of September, and September is a reminder of what I once had but didn’t have anymore. In the years after September 11, 2001, I would try to remember Augusts with my Dad. Our family of four would drive to the beach on the weekends, and my sister and I would watch Barney and Friends on the mini TV my Dad macgyvered in the backseat of his red sports car. We would spend nights at my Aunt’s house, surrounded by cousins, sitting out on their deck overlooking the river until the fireflies rose from the grass. With every passing year, I’ve wished I remembered more about him, about us, and the life that used to be. I’ll always wish I remembered more.

Despite all the good things that August harbors– birthdays, beach days, and firefly-filled nights – it’s still bittersweet all these years later. August reminds me how much I miss my Dad, our little picture-perfect American family, and how I once existed without the fear of knowing that terrible things happen to me.

The weight of this grief is something I’m much more comfortable writing about than speaking about. I spent two years during the pandemic writing what would become my essay for The Cut, “I lost my Dad on 9/11. I’m Still Searching for Who He Was”, lamenting over every sentence to encapsulate the feelings just so. Something about saying the words aloud makes it feel more real. It makes my voice quiver and my eyes well despite all the years of processing this loss and feeling these feelings again and again. Last week, I had the chance to be vulnerable and courageous and speak about this very topic at the place where all the grief began, alongside my dear friend, Chrissy (author of “Wednesday Morning”), who also lost her father on 9/11 when she was a child.

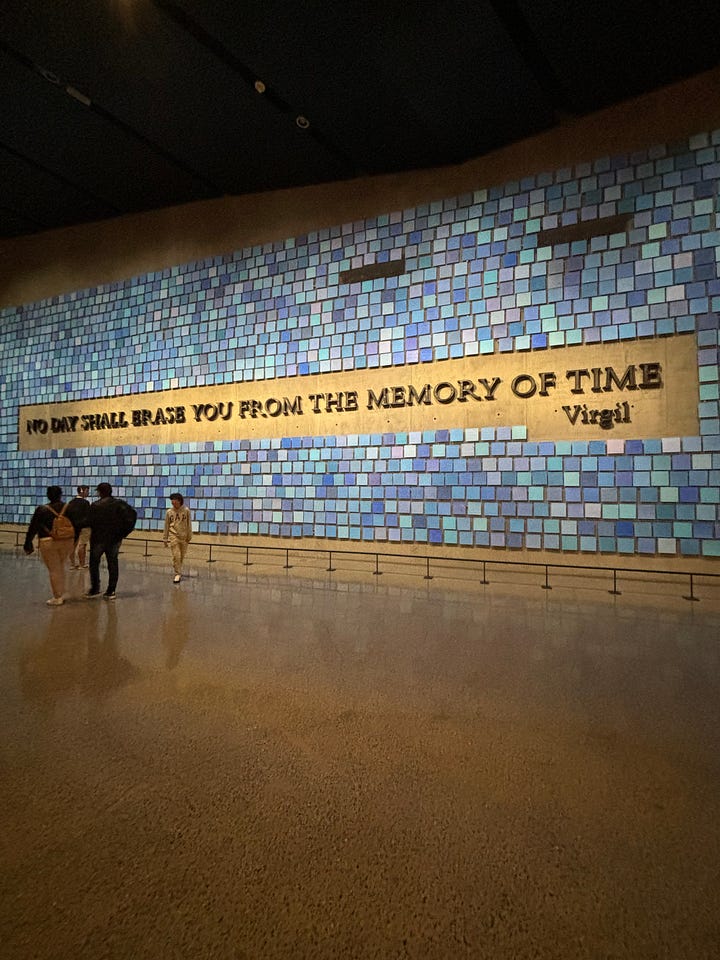

It felt fitting that I was asked to speak for an event on grief during one of the months that I feel it the deepest. That morning, I awoke before sunrise and trekked into the city via ferry. Despite the rain, I arrived at 7 am. I walked a few blocks over to the Occulus to meet my friend Chrissy and her cousin, then headed to the Memorial Museum. The memorial pools are the actual footprints of where the towers once stood. The museum itself is located in the underbelly of the World Trade Center. If you’ve ever been to either, you know how surreal it feels to be in a place brimming with human life yet has a distinct hollowness. Energetically, you can tell that what was once there is no longer there.

A few minutes before 8 a.m., museum staff welcomed us into the building, past TSA-style metal detectors, and upstairs into the atrium. A few tables were set up in a rectangle for a dozen or so people, with a nameplate for every member. I sat down with a mug of orange cinnamon tea and settled in for the ninety-minute talk. The group was intimate and thoughtful, composed of museum staff, Visionary Network members, and members of Tuesday’s Children’s network. Our “Coffee and Conversation” event kicked off with Beth Hillman, the 9/11 Memorial and Museum's president, asking Chrissy and me to share our “9/11 stories”. We both recalled our memories from that day and the days following. We echoed similar sentiments about the confusion our little brains experienced when trying to understand what was happening. How we looked to the grown-ups around us, and they, too, didn’t know how to process what was happening in this moment. We were reminded that our losses have informed the way educators and professionals address trauma in children, and our experiences have shaped the field of mental health in many ways.

The conversation flowed into honoring our experience with grief—the complicated nature of our losses and how they are simultaneously very personal and very public. There’s not a week that goes by that I don’t hear 9/11 mentioned in one way or another. It’s typically spoken about as a cultural touch point, a before and after moment, a reminder of how things used to be. It continues to be a topic in the news as new court cases continue to unfold about the acts of terror, who is responsible for them, and the justice that our families seek.

A curator at the museum asked us how the media has impacted us. I recalled a drawing I made in the weeks following the attacks. It might have been from one of the art therapy classes I took with fellow bereaved children. On the printer paper, I drew the Twin Towers, an airplane approaching, and an angel in the top right corner, signifying my Dad. I reflected on the fact that I only knew how my Dad died because the television was on, showing the same footage on a loop. I’m not sure a child who lost a parent any other way would draw an image of their final moments. A friend in the group shared that she was a college freshman at the time, and months before, she had written her college essay about how her Dad, an FDNY firefighter, was a heroic figure in her life. In the days following 9/11, her essay was leaked to The New York Post without her consent. I nodded in agreement as she described how she feels it's important to keep her Dad’s legacy alive by sharing her story with media outlets, and still, she feels conflicted with the direction their narratives can take.

Beth concluded the talk by reminding us that our stories matter. In life-changing events, news outlets and social media often pick up on the stories that are the most sensational or inspiring. Every year on 9/11, I’ll see the uplifting stories reposted on social media, like that of the Man in the Red Bandana or the rescue mission dogs. But there are hundreds, thousands of other stories that are equally worth sharing. Speaking up about my loss, my grief, and the life I am living as a 9/11 family member is how I can continue to add to the legacy of my father’s life. It’s my way of bringing humanity into an innately inhumane act, reminding those who didn’t live through it that the events of September 11th continue to have lasting impacts.

I walked away with a feeling of immense gratitude. The visionary participants and museum staff were incredibly thoughtful and present during the conversation. While the conversation was heavy, especially for an early Thursday morning, it is in connection that we are reminded of our common humanity and the role each of us plays. In my final remarks, I noted that the stories of children who lost a parent on 9/11 can be both devastating and inspiring. Being a “9/11 Kid” is a club I wish I never were a part of, but I am extremely grateful for the remarkably kind, compassionate, and resilient friends it has brought into my life. We are connected by the same terrible day, but our grief and healing are unique to each of us.

However, if we want to remember our parents and share our stories (or not), that is right. I’m still figuring out what feels best for me, too. My memoir manuscript continues to be a work in progress, with stagnant ebbs and productive flows. Conversations like this bring me back to my intention to write. Writing is the way I can reclaim a tiny portion of this infamous day, and no one can take that from me. It was an honor to speak about this, to have a dozen people sit down and listen in reverence. It reminded me that my story is worth sharing and writing about, so I’ll forge ahead.

If you’re interested in learning more about the 9/11 Memorial and Museum, you can visit their website. They have incredible resources for educators to teach about 9/11, including a 30-minute film and live chat available during school hours this September 11th. They also offer free museum admission on Mondays to New York and New Jersey residents.

If you’d like to learn more about the resilience-building offerings Tuesday Children provides to families impacted by 9/11, terrorism, and Gold Star families, you can visit their website.

I'm glad you are sharing your story.